The beginning of 1981 was the period of elections in the basic units of “Solidarity” in each enterprise. The Staszów plants were also preparing for these elections. Many of the Staszów plants used the election ordinance prepared by Bolesław Kozłowski. First the elections were held in the branches where the chairman, branch committee and delegates to the all-company meeting were elected.

On the heating branch Andrzej Ptak was elected chairman and Józef Małobęcki was elected deputy chairman. Andrzej Ptak, Bolesław Kozłowski, Józef Małobęcki, Maciej Piatkowski became delegates. A few weeks before the general election, Tadeusz Zamojski, a member of the Founding Committee, left the party after being called up for military service. There was a lack of his activity and enthusiasm in the propaganda arena.

The company trade union election of NSZZ “Solidarity” in the Sulphur Mine “Siarkopol” in Grzybów took place at the beginning of February 1981. The paper summarizing the activity of the Founding Committee was delivered by Józef Małobęcki.

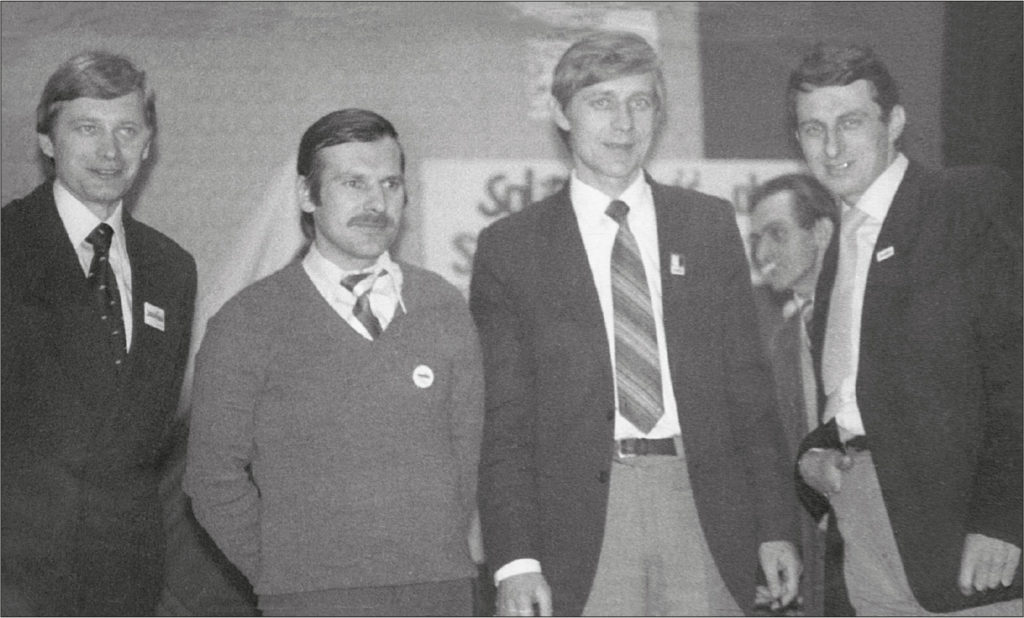

Standing from the left: Józef Małobęcki, Andrzej Ptak, Piotr Trych, Bolesław Kozłowski.

During the meeting, three permanent incumbents were elected by secret ballot, delegated exclusively to union work: a chairman, a vice-chairman, and a secretary:

Bolesław Kozłowski – Chairman – Heating Branch

Józef Małobęcki – Deputy Chairman – Heating Branch

Anna Czerwiec – Secretary – “Z” mining field

The union presidium, company branch of the Solidarity Trade Union, audit committee and delegates to the regional convention were also elected. According to the ordinance, the branch presidents automatically became members of the company branch of the Solidarity Trade Union.

Apart from them, the company branch of NSZZ “Solidarity” in the Sulphur Mine “Siarkopol” in Grzybów consisted of 54 members:

Andrzej Ptak – Heating Branch – Chairman

Tadeusz Ratusznik – W-S Field – Chairman

Stanisław Pitek – Z Field – Chairman

Maciej Franke – Refining – Chairman

Zbigniew Kowalik – Communication – Chairman

Wanda Ojdana – Workers’ Hotels – Chairman

Józef Kowalik – Administration – Chairman

Michał Socha – Procurement – Chairman

Czesław Forkasiewicz – Energy and Mechanical Equipment – Chairman

Marian Patrzałek – Railway Branch – Chairman

Marek Zdziuch – Electrical Maintenance – Chairman

Henryk Wrona – ZOW – Chairman

Kazimierz Mnich – ZBR – Chairman

Tadeusz Podgórski – Transport – Chairman

Adam Chmiel – Mechanical Workshop – Chairman

Tadeusz Dubiel – Heavy Equipment – Chairman

Marek Kosiński – Fire Brigade – Chairman

Andrzej Kudla – Laboratories – Chairman

Marian Piątkowski – Retirees & Pensioners – Chairman

Henryk Maciejski – Boiler Maintenance – Chairman

Piotr Trych – CS2 Plant – Chairman

Stanisław Mikolajczyk – CS2 Plant

Zdzisław Witas – Reclamation

Tadeusz Madej – A-Z Field

Andrzej Lis – Mechanical Maintenance

Maciej Piątkowski – Heating Branch

Aleksandra Cukierska – Laboratories

Kazimierz Myśliwiec – W-S Field

Stanisław Jastrząb – Administration

Jan Lampart – Transport

Halina Wiktorowska – Procurement

Barbara Gąsior – Reclamation

Mieczysław Baczewski – Electrical Maintenance

Gerard Dworecki – Procurement

Tadeusz Kozioł – Mechanical Workshop

Czesław Kaszluga – Boiler Maintenance

Stefania Polniak – Electrical Maintenance

Leopold Topolski – ZOW

Jerzy Zieliński – Mechanical Workshop

Wiktor Poniewierski – Procurement

Wiesław Bednarek – ZBR

Józef Słomka – A-Z Field

Czesław Dzieciuch – Heavy Equipment

Wojciech Adamiec – Heating Branch

Andrzej Czeczot – Mechanical Workshop

Marian Stępień – Administration

Marian Żak – Refining

Jan Bugaj – Refining

Barbara Skrzynecka – Administration

Marian Pyciarz – Mechanical Workshop

Zdzisław Grelewski – Heating Branch

The following were appointed to the presidium:

Andrzej Ptak

Piotr Trych

Tadeusz Ratusznik

Stanisław Pitek

Mieczysław Baczewski

Michał Socha

Halina Wiktorowska

Kazimierz Myśliwiec

Jan Lampart

Maciej Franke

Wiktor Poniewierski

Aleksandra Cukierska

Marian Patrzałek

An audit committee was elected consisting of:

Władysław Uśmiał

Wacław Borowik

Stanisław Fołda

Jan Tubis

Mieczysław Popiołkiewicz

Eugeniusz Witaszek

The delegates to the regional convention of the “Sandomierz Land” Region were:

Bolesław Kozłowski

Józef Małobęcki

Piotr Trych

Andrzej Ptak

Halina Wiktorowska

Marian Pyciarz

Wiktor Poniewierski

Stanisław Pitek

Marian Pyciarz was elected Social Labor Inspector.

After the elections, the union finally found better premises. The company management gave the union 3 office rooms in the management building, opposite the Chemists’ Union Thus, the union had found “good” company, without paying much attention to this fact, as from that moment on, it was the dominant force in the Grzybow sulfur mine.

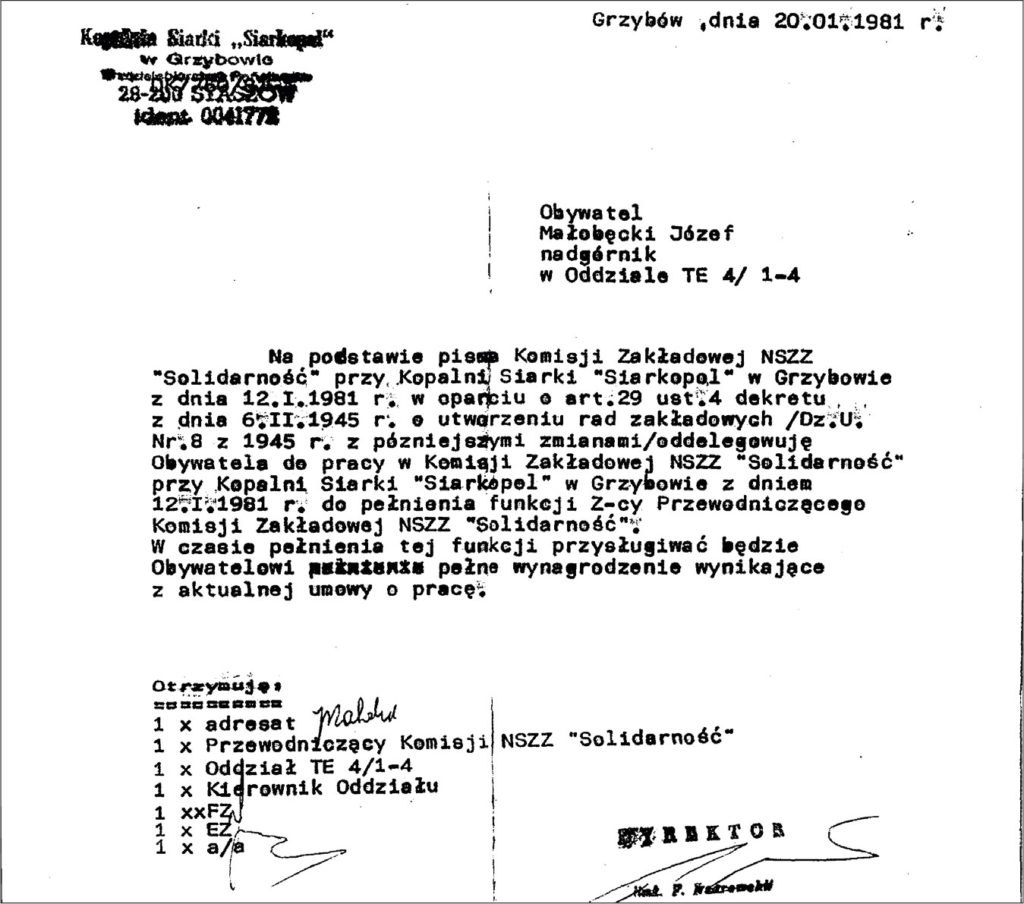

Engagement of Józef Małobęcki as deputy chairman of the Solidarity Trade Union at the Sulfur Mine.

From the moment Solidarity was established at the mine, no decisions of the management concerning labour matters could be taken without consulting the union. Above all, it was necessary to break with the previous manipulative principle of collective voting, because there was a risk that, due to the number of communist organizations existing in the company, Solidarity could be outvoted. It became a rule that decisions would be made by the management

regardless of the group (management, trade unionists, party), and Solidarity would respond to this.

Bolesław Kozłowski, as chairman, dealt with social and salary matters in the company. Anna Czerwiec, by virtue of her function, dealt with organizational matters. Józef Małobęcki combined both functions, taking care of current intervention issues, as well as supervising propaganda matters and protecting union activities and interests. For this purpose, at his request, a telex was installed in his office and a connection with the plant’s radio station was set up, thanks to which announcements, statements and resolutions of the trade union authorities were directly transmitted by telephone throughout the company.

The only department without a branch committee of Solidarity was the department of the partially militarized industrial guard, where the heavily Communist management imposed discipline by intimidation. In this section of the plant only one worker was a member of Solidarity. This was a negligence on the part of the Founding Committee, which had to be quickly corrected, and for which there was not enough time before the imposition of martial law.

“Solidarity” in the mine continued to build the strength of its structures by convening meetings of the company branch, creating a section for occupational health and safety, wage matters, housing, social and welfare issues. The enormity of problems was so great that it exceeded the time capabilities of the three people delegated to union work. The section consisted of people who were members of the Company Branch. The work and organizing the section was a laborious process and required time. This was due to reasons that were not always within the control of the committee members. The mine worked in a 4 brigade system. The vast majority of the Commission worked in shifts. For this reason, participation in the work of the company branch of the Solidarity Trade Union often became questionable. There were also chronic shortages of supplies, unbelievable from today’s perspective. There were permanent

market shortages in all kinds of goods, both food and industrial. These shortages were caused by two reasons. The first was the dilettantism, incompetence and ineptitude of the communist authorities in their management to date. The second was the deliberate concealment and hoarding of goods. This perfidious manipulation was calculated to make the society tired and to shift the responsibility for the shortages in supply to the unions, as it was the unions who organized strikes that harmed production. This was another typical premeditated manipulation by the communist authorities. The life of Polish society at that time consisted of the constant search for products necessary to live. This problem also affected the members of the company branch, which meant that attendance at its meetings was not always satisfactory.

During this time, Solidarity at the mine played a controversial role. Manipulated by the bodies (including the union bodies), the union proceeded to distribute company housing, which it should not have done since it was not the owner of the housing. Too many of the mine’s workers were waiting to be assigned housing or to exchange it. Among these workers were also members of the company branch of the Solidarity Trade Union. An unacceptable paradox occurred here. The unions were allotting apartments from the company housing pool, not their own, and instead of the unions, the management became the defender of workers’ interests. The procedure for allocating apartments was ostensibly intended to shorten the waiting time, as giving opinions on the management’s decisions was supposed to unnecessarily lengthen the period of settling into these apartments. In the end, on the days the director received employees, there was a long line of people at the management’s secretary office, complaining about the allocation of apartments made by the unions. The paradox of this situation was that the management became the defender of the union members. This was a complete contradiction of the goals and ideals of the Solidarity union. It was an unforgivable mistake that cast a shadow over the reputation of the union not only in the mine but also in the whole Staszów region. Understandable criticism resounded in the company and in other Staszów plants. Among the union’s intervention activities at the mine at that time was the appointment of a committee to verify and solve the problem of moisture in the apartments on the “East” estate. As a result of the inspection these facts were confirmed, thus it was decided to insulate the blocks from the outside during their plastering. The mine’s “Solidarity” worked for the recognition of workers’ respiratory diseases as an occupational disease. For this purpose, the deputy chairman, Józef Małobęcki, asked Solidarity at the Medical Academy in Cracow to send a commission to confirm it with appropriate, independent tests.

Józef Małobęcki as a chairman of the “Staszów Land” region and as a deputy chairman of the “Solidarity” union in the Sulfur Mine, went quite often to the headquarters of the “Sandomierz Land” region in Stalowa Wola. During one such trip, he and other members of the region’s management board were arrested in Tarnobrzeg and accused of transporting illegal anty communists literature with the intention of distributing it. After several hours in the building of the Provincial Headquarters of the Militia, they were released. On the next day, the staff of the enterprise was informed about the repression in a specially issued announcement. It was followed by a sharp confrontation between Józef Małobęcki and Franciszek Nadrowski, the director of enterprise, who strongly objected to the publishing of such “unverified” information without his knowledge.

The objection was rejected. Simultaneously, the Staszów Land Coordination Committee was active, and its weekly meetings were held in the plant club of the Sulfur Mine at Langiewicza Street. The purpose of meetings was to increase the effectiveness of actions, and to prepare for a wider scale of activities. Around the same time, Józef Małobęcki was approached by Stanisław Żyła from the village of Poddębowiec, who asked for help in organizing the Independent Self-Governing Farmers’ Union “Solidarity” in the “Staszów Land.” It was difficult to reconcile the overload of duties with the new task, and it was also difficult to refuse such a request. The first meetings with Stanisław Żyła were rather limited to giving advice, but later they turned into greater involvement. In March 1981 another provocation took place, known as the “Bydgoszcz provocation,” which had very dangerous consequences

for the union and especially for Poland. It happened in the following, briefly presented, circumstances.

The emergence of the workers’ Solidarity activated individual farmers, seeking to establish an organization along the lines of the workers’ Solidarity union to represent their interests. Farmers organized into founding committees and demanded that the communist authorities register their union organization, Solidarity. Unlike the uniform “Solidarity” of the workers, the farmers were organized in the NSZZ “Solidarity of Individual Farmers” and in the Tarnobrzeg district in the NSZZ “Rural Solidarity,” headed by the aforementioned veteran of anti-communist activity in the countryside – Jan Kozłowski. It was known that the threat to the Communists posed by Workers’

Solidarity would increase disproportionately once organized farmers, those true breadwinners of the nation who had always been in deep opposition to Communist power, registered. Contempt for their labor, the imposition of taxes and insurance premiums were common methods used to push them off the land.

The Solidarity Trade Union, as the aforementioned socio-political movement, could not fail to support the aspirations of farmers, who were guided by the same ideological principles and aimed at the same goals. At that time, farmers’ representatives from all over Poland led an occupational strike in Ustrzyki Dolne, demanding the registration of their union organization. In addition to the areas of southeastern Poland, where farmers’ pressure was traditionally strongest, farmers’ union activity developed in Radom, Mazovia, and Bydgoszcz. The chairman of this region, Jan Rulewski, was invited to a session of the provincial national council in Bydgoszcz. His task was to take

a speech and present the aspirations of Solidarity in this region as well as to lend support to Solidarity of Individual Farmers. During the session, Jan Rulewski and other representatives of the region were severely beaten by officers of the Civic Militia. The presence of the Militia, which had never and nowhere before taken part in any council session, was not accidental. The whole action that ended with the beating was prepared in detail, which is evident from later accounts. The union, using its statutory rights, applied the final defense it was entitled to, announcing a warning nationwide strike and preparing for a general strike. A general strike was a last resort in case the inspirers of this provocation were not identified and punished. The question arose. Who prepared this provocation and why?

The society was divided. It should be mentioned that previously appointed Prime Minister of the communist government, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, was at the same time Minister of Defense, and a little earlier he had been “elected” Secretary of the communist Polish United Workers’ Party. As a result, he had all the most important attributes of power in Poland at that time. Wojciech Jaruzelski was minister of defense in the government of Władysław Gomułka and it was his order that the army took part in suppressing the anti-communist protest in Gdańsk in 1970. It was known that this provocation was not prepared by someone at a lower level, such as the Voivodeship Headquarters of the Civic Militia in Bydgoszcz, but the decision to carry it out could only have been made at the highest level of the communist hierarchy. The basic question was also what role Wojciech Jaruzelski played here? Did he know about this provocation and was he its organizer? Was it also a provocation against his actions in relation to Solidarity, considered by the socalled “party concrete” to be too soft. Why did this provocation took place? It was probably a sensor and a test of communist authorities on the society, which was supposed to answer the question: How far can one go in the fight with the society and what will be its response. A determined society responded with a warning strike. Exactly at the same time a meeting was held in the City Hall

of Staszów between the Head of City, Władysław Szeliga, and members of the Company Committee of the mine: Józef Małobęcki and Andrzej Ptak. The meeting concerned the illegal occupation of a company apartment by a Staszów resident who is not a mine employee. Extremely hard and difficult living situation, intensified by a personal tragedy forced this man to take such a step. From the moral point of view it was a very ungrateful, unpleasant and embarrassing situation for the trade unionists. However, it was a company apartment, already granted to a mine worker. Permission to occupy it would have set a precedent of settling “wildly” apartments belonging to others. Therefore, despite our full sympathy and understanding of the situation, the trade unionists demanded that the apartment be vacated. In such human misfortunes trade unionists had to participate and act. It was a very ungrateful and unpleasant situation, caused by no one, but the inept and ineffective communist authorities, who could not help the nation’s living conditions despite their 40-year-long promises. The meeting in the City Hall

was interrupted by a phone call from Anna Czerwiec, the secretary of the Workers’ Committee, who was carrying out the orders of the National Committee of the Union, ordering the breaking of all talks with the authorities of all levels in the whole country because of the events in Bydgoszcz.

Preparations for a general strike throughout the country began. In the absence of Bolesław Kozłowski, the chairman of the mine’s union, who was often sick, the responsibility for the strike fell on his deputy, Józef Małobęcki, who as the chairman of the “Staszów Land” Local Coordination Committee, also coordinated the strike in other Staszów plants. Reliable helpers in coordinating the strike turned out to be the union founders Andrzej Ptak and Piotr Trych, who alternated with other members of the Works Commission and were on duty in the mine 24 hours a day until the general strike was called off. These duties were necessary because of the possibility of provocative sabotage. Due to the nature of work in the mine, it was impossible to stop the work in the direct production departments. However, work in the supporting branches was stopped. Access to any branch by outsiders who did not work in those branches was allowed only to those who had a pass issued by the company branch of the Solidarity Trade Union. Under these circumstances, an unusual event in the life of mine took place, when the plant secretary of

the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR), Henryk Winiarczyk, the “first man after God” in the mine, who had the right to enter every department under any circumstances, was not allowed into the Boiler Room Maintenance Department, as he did not have an authorization pass. Informed of this fact, the director of the mine, Franciszek Nadrowski, rushed like a storm into the office of the Strike Committee shouting: “Gentlemen, I’m losing my mind with you!” It was difficult for the “notables” to come to terms with the new reality.

The general strike did not take place, although some of its signs were already visible. The so-called “Warsaw Accord” took place between the union leader, Lech Wałęsa and Mieczysław Rakowski, who represented the communists. The Polish Episcopate, headed by Primate Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, took an active part in the mediation leading to the conclusion of this agreement. At the same time, large-scale maneuvers of the northern group of Soviet troops were taking place just outside Poland’s borders. The “Bydgoszcz provocation” somehow strangely coincided with these maneuvers. Lech Wałęsa’s arbitrary decision to suspend the general strike was received by the trade unionists with conflicting feelings. This decision probably stemmed from the fear of accelerated Soviet intervention in Poland. For this arbitrarily made decision, in March 1981, Lech Wałęsa had to explain himself at the First National Congress of NSZZ “Solidarity” in Gdańsk Olivia Hall. It must be admitted that once again in history the situation for Poland was very dangerous. A positive result of the events that took place was the registration of the NSZZ “Solidarity” of Individual Farmers.